“Wandering lines.” Conversazione con Andrew Kötting

in collaborazione con il progetto di ricerca cinematografica ⇨ La Camera Ardente

L’arte di Andrew Kötting è fulgido esempio di come l’indirizzo cinematografico non possa mai pienamente appartenere a se stesso, al laccio stretto dei propri luoghi marcati o rilevati, finendo così per spillare altrove, per mischiarsi con gesto del vagare, alimentando altri vasi traboccanti. Erede di Derek Jarman, Kötting porta la sua carovana di fotogrammi attraverso la fitta notte della storia umana. Gli fanno compagnia (in questa nomadia edificata di opera in opera) altri viandanti: Alan Moore, Iain Sinclair, Stewart Lee, Ben Rivers… quasi una comunità impegnata a far cantare sentieri. E poi c’è sua figlia Eden, che è ospite privilegiato in questa conversazione…

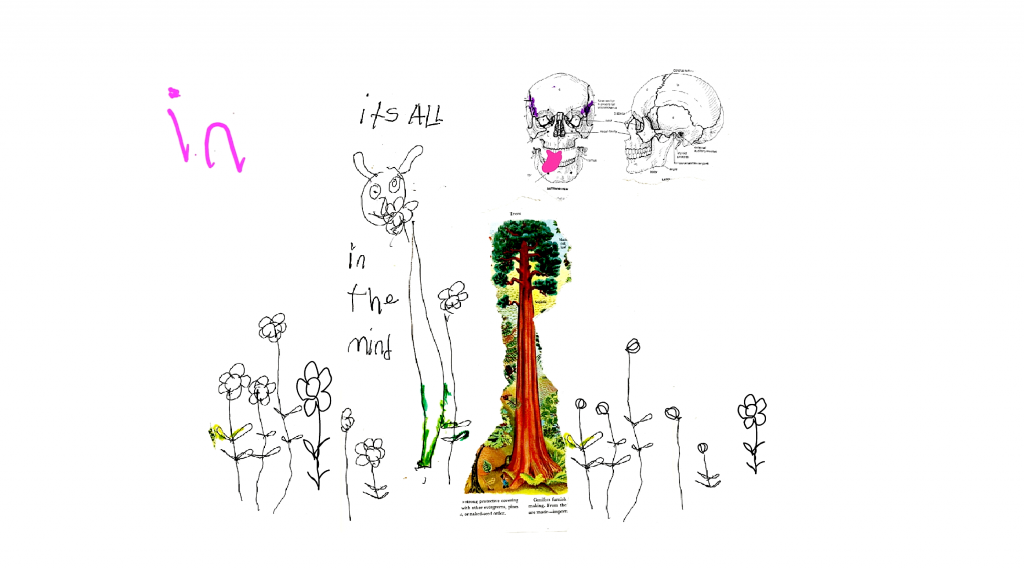

Salve, Andrew. Inizierei questa conversazione dalle linee vaganti che attraversano la superficie della tua arte. Non mi riferisco soltanto ai viaggi o ai pellegrinaggi dei tuoi film (il cammino di 90 miglia percorso da John Clare in “By our Selves”, per esempio), ma anche ai disegni di tua figlia Eden che tu hai elaborato per altri lavori (come il magnifico “Dog Ate Dog”) e ai vostri libri quasi animati. Il cinema ha un luogo, o è forse una soglia tra le cose?

Da dove incominciare? Forse i “Journey Works” (Jaunt – Gallivant – Swandown – Offshore – By Our Selves e Edith Walks) potrebbero essere visti come la mia versione delle “songlines”, le vie dei canti di Bruce Chatwin:

“Il nostro errare ha sparso le vie dei canti per tutto il globo (generalmente da sud-ovest a nord-est), raggiungendo infine l’Australia, dove ora sono preservate nella cultura più antica del mondo”

I “Journey works” sono il mio tentativo di definire, descrivere, disporre e delineare i paesaggi attraverso i quali mi muovo con la mia famiglia e i miei amici. Essi sono psicogeografici nella natura e attingono dalla mia esperienza nell’emisfero settentrionale (ma soprattutto qui in UK). Sono pertanto influenzati dal folkloristico, dal reale, dall’irreale, dal mitologico e dall’allegorico, e dipendono dalla mia fascinazione verso il comporre le cose direttamente mentre si procede nel cammino, verso l’improvvisazione, il collage e, in ultimo, verso il processo di editing e d’ingegneria inversa per produrre senso e ordinare l’evento, sia esso un pellegrinaggio o un happening.

Sono anche attirato dal carnale, dal corporeo e dall’elementare come mezzi di produzione. Devi esserci resistenza, risonanza, assurdità e difficoltà in egual misura, ed è attraverso questo processo che il lavoro viene realizzato.

Ho creato un mio ⇨ “alphabetrarium” che potrebbe essere d’aiuto per comprendere quanto sto dicendo…

E per quanto riguarda il lavoro che sto facendo con mia figlia Eden, posso dire che è un modo di celebrarla e stimolarla come essere umano e come artista. Nonostante la sua severa disabilità e i suoi limitati mezzi di comunicazione, io spero di trasportare il pubblico nel regno dell’Altro dove nuove maniere di osservare ed ascoltare possono essere vissute. I suoi disegni e i suoi dipinti sono connessi tematicamente ai vari progetti ai quali sto lavorando singolarmente, ma i film che realizziamo insieme riguardano tanto “un’atmosfera” quanto l’atto di raccontare storie.

Esiste certamente un luogo per il cinema ma nel mio lavoro sono molto più interessato a rompere le convenzioni di ciò che il cinema “mainstream” è divenuto. Voglio condurre il mio pubblico in luoghi dove le persone non sono mai state. Il suono è la chiave…

Nel tuo alphabetrarium scrivi: “M sta per realtà multiple, disfunzioni audio / visive, fessurazioni in sequenza e tagliar via il lineare per scoprire che molte cose sono possibili”. Cosa significa tagliare e perforare il “lineare” nell’era dell’immagine digitale e di Internet, che potrebbe essere già considerato un dispositivo nomade?

Sospetto che intendessi: “girovagare e vagabondare come meditazioni organizzate ma scadenti – con gli Angeli del Caso come guida o bussola …!”

Quali sono le altre maniere di osservare ed ascoltare che tua figlia Eden ti ha indicato?

Eden disegna, dipinge e crea collage perché ciò le porta felicità, gioia e senso di realizzazione. È anche una terapia per entrambi, tiene cioè il cane nero lontano dalla porta: se non avesse interesse per queste cose penso che sarei impazzito molto tempo fa. Eden è entusiasta nel guardare i suoi disegni prendere vita – il fatto che si muovano la fa ridere -, e anche se ha ben poca consapevolezza della complessità della mia ambizione (quando sovrappongo il suono e le voci nel tentativo di dare al lavoro un ‘significato’ o una messa a fuoco), a lei piace il fatto che ci sia molto da fare…forse un buon esempio di questo processo è il film che ho fatto insieme al mio amico Ben Rivers, che Eden conosce oramai da molto tempo e ama impressionare.

Eden ha poca comprensione del sottotesto filmico, della sua ambizione esistenziale o della critica dei sistemi di credenze religiose creati dall’uomo monoteista, ma se lei è con un pubblico che ride è felice della reazione divertita, ed è questa innocenza che mi fornisce un ingrediente vitale per la collaborazione: la nostra relazione funziona come se stessi lavorando con del materiale d’archivio o found-footage, ma naturalmente sono in grado di incoraggiare Eden a lavorare su di un tema specifico. Quando sono presente nella colonna sonora o quando -vestito da Orso di Paglia- le stringo la mano mentre camminiamo lungo una spiaggia, allora il potere della nostra relazione padre / figlia inizia a prendere piede e un’altra serie di emozioni viene vissuta dal pubblico. C’è il paradosso di una collaborazione tra un “artista insider” e un “artista outsider” al lavoro, e questo elemento è qualcosa che manifesta nuove e “altre” qualità.

Nei tuoi film, la critica dei “sistemi monoteistici” che hai citato è attivata attraverso una coagulazione di immagini le cui radici si intrecciano, quasi fossero zone indiscernibili tra di loro. È possibile “superare” questa realtà monoteistica attraverso il cinema?

Tutto può essere superato nella vita e non solo nel cinema, anche se alcune cose richiedono molto più tempo!

La gioia di essere nati!

Una vita piena di anatemi e ammirazioni!

Continuiamo a prescindere a dire sciocchezze – le parole sono vitali – specialmente quando tentano di indebolire i sistemi monoteistici (monotheisticemansystems) che si riappropriano continuamente di tutti i cambiamenti in un disperato tentativo di fingere che tutto fosse già nel loro grande Libro fin dall’inizio perché il profeta ha detto così e così!

Le collaborazioni (Alan Moore, Iain Sinclair, Stewart Lee …) sono una componente cruciale del tuo cinema. L’atto di fare un film è l’invenzione di una comunità a venire?

Le collaborazioni sono sempre state una parte vitale del mio processo: meno l’invenzione di una comunità a venire quanto piuttosto la base della mia evoluzione. Senza di loro mi sento privato di qualcosa, forse perché avendo Eden nella mia vita sono sempre aperto all’apparire dell’Altro.

Le varie abilità che i collaboratori apportano al lavoro sono allo stesso tempo positive e stimolanti. La loro generosità di spirito e la fiducia nelle mie ambizioni è anche molto rassicurante. Potrebbe essere perché sono consapevole che ogni progetto è sempre e solo un’approssimazione di ciò che pensiamo o vogliamo. I risultati non sono prescrittivi e la loro contingenza significa che c’è sempre spazio per permettere che le cose accadano. C’è molto spazio anche per l’improvvisazione, perfino se sto lavorando con una sceneggiatura, e ciò ci consente di perfezionare o aggiungere altri passaggi.

Stewart Lee riassume perfettamente tutto ciò alla fine del film “Swandown”, quando dice: “Penso che Andrew Kötting veda solo quello che succede, invertendo poi l’ingegneria del significato una volta che ha collezionato e messo insieme i frammenti dell’evento …”

Dato che “c’è molto spazio per l’improvvisazione”, pensi che un film debba essere un progetto senza fine, qualcosa sempre aperto all’essere rovesciato?

Certamente! In effetti tutte le opere finiscono per alimentarsi a vicenda. Le immagini traboccano. Il lavoro è senza fine sino a quando decido di portarlo a termine; ma anche in quel momento il film potrebbe andare avanti ancora un po’, per poi spegnersi definitivamente. La finitudine abbonda:

“N sta per narrativa Non finita, né una cosa e neppure l’altra. N sta per ‘da una parte all’altra’ dentro le Neverneverlands dello spillamento, oltre le polemiche e la critica storica. N sta per Nuovo e Nomadico, ma anche per continuare a far girare la storia creativa dell’umanità. N sta per i Nuovi racconti dalle end-zones e per le storie Notturne tessute dal fuoco per scavare nella torba più oscura!”

Conversazione a cura di Giorgiomaria Cornelio

In collaboration with ⇨ La Camera Ardente

Andrew Kötting’s art is a luminous example of how the cinematographical project could never fully belong to itself and to its narrow boundaries, thus spilling elsewhere, becoming one thing with the act of wandering. Like Derek Jarman, Kötting leads his caravan of frames through the thick night of humanity. In this nomadic travel built “film after film”, there are other wanderers that make the paths sing a never-ending poem: Alan Moore, Iain Sinclair, Stewart Lee, Ben Rivers, and of course Eden Kötting, who is a special guest of this conversation.

Hello, Andrew. I would like to begin this conversation from the wandering lines that pass through the very surface of your art. I am not referring only to the journeys or the pilgrimages of your films (the 90-mile walk of John Clare in “By Our Selves”, for example), but also to the drawings of your daughter Eden that you edited for other works (like the marvellous “Dog Ate Dog”) and to your quasi-animated books. Does cinema have a place? Or -maybe- is it a threshold between things?

Where to begin?! Perhaps the ‘Journey Works’ (Jaunt – Gallivant – Swandown – Offshore – By Our Selves and Edith Walks) might be seen as my versions of ‘songlines’.

“Our wanderings spread “songlines” across the globe (generally from southwest to northeast), eventually reaching Australia, where they are now preserved in the world’s oldest living culture”.

They are my attempt at defining, describing, deliberating and delineating the landscapes that I move through with friends and family. They are psychogeographical in nature and draw upon my own experiences here in the northern hemisphere, but perhaps more importantly here in the UK. They are informed by the folkloric, the real, the unreal, the mythological and the allegorical and they are dependent on my fascination with making-things-up-as-I-go-along, improvisation, collage and ultimately at the edit stage, the process of reverse engineering to make sense and order of the event, pilgrimage or happening.

I’m also drawn to the physical, the corporeal and the elemental as a means of making. There has to be endurance, resonance, absurdity and difficulty in equal measure, and it is through this process that the work gets made….

I’ve created ‘an ⇨ alphabetrarium of kötting’ that might help.

And as far as the work that I have been making with my daughter Eden, it is a way to activate, stimulate and celebrate her as an artist and human being. Despite her severe disability and limited means of communicating I hope to transport the audience into the realms of the ‘other’ where new ways of looking and listening might be experienced. Her drawings and paintings are thematically connected to the various projects that I might be working on but the films that we make together are as much about ‘atmosphere’ as they are about story telling.

There is a place for cinema in my work but I am more interested in breaking with the conventions of what mainstream cinema has become. I want my audiences to be taken to a place that they have not been before. The sound is key….

In your alphabetrarium, you write: “M is for Multiple realities, audio/visual dysfunction, fissures in sequence, and cutting away from the linear to discover that most things are possible”. What does it mean to cut and pierce the “linear” in the age of the digital image and the Internet, which could be already considered a nomadic device?

I suspect that I meant: meanderings and wanderings as organised yet shoddy musings – with the Angels of Happenstance as guide or compass…!

What are the ‘other’ new ways of looking and listening that your daughter Eden has indicated to you?

– Eden draws and paints and makes collage because it brings her happiness and joy and a sense of achievement – it is also therapy for the both us – it keeps the black dog away from the door – if she had no interest in these things then I think I would have gone mad a long time ago – with the films that we make together she is also excited by watching her drawings come alive – the fact that they move makes her laugh – she has very little understanding of the complexities of my ambition when layering the sound and voices in an attempt to give the work ‘meaning’ or focus BUT she likes the fact that there is a lot going on….perhaps a good example of this process is a film I made together with my friend Ben Rivers – who Eden has known for a very long time and likes to impress.

Eden would have little comprehension of the film’s subtexts or its’ existential ambition or critique of monotheistic manmade religious belief systems – BUT if she is with an audience and they laugh she is just happy that they laugh – and it is this innocence that provides me with a vital ingredient for the collaboration – the relationship works in a similar way to the way in which I might work with archive or found-footage BUT of course I am in a position to encourage her to work to a specific brief or theme. When I am present on the soundtrack or dressed as a Straw Bear and holding her hand as we walk along a beach, then the power of our father/daughter relationship begins to take hold and another set of emotions are experienced by the audience. There is the paradox of a collaboration between an ‘insider artist’ and an ‘outsider artist’ at work and this is something that offers the work new and ‘other’ qualities.

In your films, the critique of the “Manmade monotheistic mansystems” is activated through a coagulation of images whose roots are intertwined like areas of indiscernibility. Is it possible to “overcome” this monotheistic reality through cinema?

Everything can be overcome in life and not just in cinema, some things just take a lot longer!

The joy of being born!

A life full of anathemas and admirations!

We blunder on regardless – words are vital – especially when they attempt to undermine the ongoing monotheisticemansystems which continually re-imagine and re-appropriate all THE changes in a desperate attempt to pretend that ALL was there in THEIR BIG book from the get-go because THE prophet said so!

Collaborations (Alan Moore, Iain Sinclair, Stewart Lee…) are a crucial component of your cinema. Is the act of making a film the invention of a community-to-come?

Collaborations have always been a vital part of my process – less the invention of a community-to-come rather the bedrock of my evolution. Without them I feel bereft, perhaps it is because having Eden in my life I’m always open to the ‘opening up’ of the ‘other’. The various skills that the collaborators bring to the work is both life-affirming and inspiring. Their generosity of spirit and indeed trust in my ambition is also very reassuring. It might be because I’m content in the knowledge that each project is only ever an approximation of what I think I/we want. The outcomes are not prescriptive and their contingency means that there is always room to allow things to happen. There is much room for improvisation, even if I am working with a script and this affords plenty of room for adjustment and addition. Stewart Lee sums it up perfectly at the end of the Swandown film when he says: I think Andrew Kötting, he just sees what happens and reverse engineers the meaning once he’s collated the event….

Since “there is much room for improvisation”, do you think that a film should be a never-ending project, something always open to being upturned?

YES – indeed all works feed in and out of each other. Spillage abounds. The work is never-ending up until the point that I end at which point it might well blunder on for a little longer and then end. Endness abounds!

“N is for never a finite narrative, neither one thing nor another. N is for hither and dither within the Neverneverlands of spillage, post polemics and critical histories. N is for NEW and Nomadic and keeping the creative human story turning. N is for new tales from the end-zones and night-time fire-yarns for folk to dig into like the darkest peat.”

Interview by Giorgiomaria Cornelio